August 01, 2018

Major Terms Defined

Before drafting a trust, the draftsperson must have a basic understanding of the people involved, and the role of each person in the administration of the trust. Selected definitions under NY Surrogate’s Court Procedure Act (SCPA) §103 (for purposes of the SCPA) follow:

- Beneficiary. Any person entitled to any part or all of an estate.

- Corporate trustee. Any trust company, any bank authorized to exercise fiduciary powers and any national bank having a principal, branch or trust office in this state and duly authorized to exercise fiduciary powers.

- Fiduciary. An administrator, administrator c.t.a., administrator d.b.n., ancillary administrator, ancillary administrator c.t.a., ancillary executor, ancillary guardian, executor, guardian, preliminary executor, temporary administrator, testamentary trustee, to any of whom letters have been issued, and also the donee of a power during minority and a voluntary administrator and a public administrator acting as administrator or a public administrator or county treasurer to whom letters have been issued, and a lifetime trustee.

- Grantor. The creator of a lifetime trust.

- Individual trustee. Any trustee who is not a corporate trustee.

- Lifetime trust. An express trust, including all amendments thereto, created during the grantor's lifetime other than a trust for the benefit of creditors, a resulting or constructive trust, a business trust where certificates of beneficial interest are issued to the beneficiary, an investment trust, voting trust, a security instrument such as a deed of trust and a mortgage, a trust created by the judgment or decree of a court, a liquidation or reorganization trust, a trust for the sole purpose of paying dividends, interest, interest coupons, salaries, wages, pensions or profits, instruments wherein persons are mere nominees for others, or a trust created in deposits in any banking institution or savings and loan institution.

- Lifetime trustee. A trustee acting under a lifetime trust.

- Property. Anything that may be the subject of ownership and is real or personal property, or is a chose in action.

- Testamentary trust. A trust created by will.

- Testamentary trustee. Any person to whom letters of trusteeship have been issued.

- Trust. A testamentary trust or a lifetime trust.

Major Laws Governing Creation and Administration of Trusts

Article 7 of the NY Estates, Powers and Trusts Law (EPTL) governs the administration of trusts in New York State. Also of importance to the administration of trusts are EPTL Article 11 (Fiduciaries: Powers, Duties and Limitations) and Article 11-A (Uniform Principal and Income Act). Sections of note include:

- EPTL §7-1.4: An express trust may be created for any valid purpose.

- EPTL §7-1.9(a): Upon the written, acknowledged consent of all persons beneficially interested in a trust (grantor, trustee, current and presumptive remainder beneficiaries), the grantor can amend or revoke an otherwise irrevocable trust (in whole or in part). Only permissible if all persons beneficially interested are competent adults.

- EPTL §7-1.12: Supplemental Needs Trust (to be discussed in further detail separately).

- EPTL §7-1.14: Any person (a natural person, an association, board, any corporation, court, governmental agency, authority or subdivisions, partnership or other firm and the state under EPTL §1-2.12) may by lifetime trust dispose of real and personal property. A natural person must be at least age 18.

- EPTL §7-1.16: A lifetime trust is irrevocable unless it expressly provides that it is revocable.

- EPTL §7-1.17(a): A lifetime trust shall be in writing and executed and acknowledged by the grantor and at least one trustee (who may be grantor) in the manner required for the recording of a deed; or in lieu of acknowledgement, 2 witnesses.

- EPTL §7-1.18: A lifetime trust is valid as to any assets therein to the extent the assets have been transferred to the trust.

- EPTL §7-1.19(a): Any trustee or beneficiary may petition to terminate an uneconomical trust.

Who are the Main Parties? Their Duties and Responsibilities to a Trust

The main parties to a trust are the grantor (the person who created the trust), the Trustee (the person managing the trust), and the beneficiaries (the person for whom the trust was created and who has a beneficial interest in the trust assets). When reviewing a Trustee’s actions, it is important to remember that not only must the effect on the current beneficiaries be considered, but also that of the presumptive and contingent remainder beneficiaries. EPTL Article 11 includes the powers, duties and limitations of Trustees.

- EPTL §11-1(b): a detailed list of Trustees’ powers is included here and should be reviewed. If additional powers are required, they should be expressly included in the trust document.

- EPTL §11-1.6: Every fiduciary shall keep property received as a fiduciary separate from his/her individual property. EPTL §11-2.1 (the Principal and Income Act) sets forth how trust assets and expenses are allocated between income and principal.

- EPTL §11-2.1: The determination of a receipt or disbursement as principal or income (or partly to each) is governed first by the trust instrument; or in accordance with EPTL §11-2.1 (if not specified in trust); or in accordance with what is reasonable and equitable to those entitled to income and principal. EPTL §11-2.1(a)(1). If the trust instrument gives the Trustee discretion in crediting a receipt or disbursement to income or principal (or partly to each), no inference that the Trustee has or has not improperly exercised such discretion arises from the fact that the Trustee made an allocation contrary to EPTL §11- 2.1.

- EPTL §11-2.1(b)(1): defines income as the “return in money or property derived from the use of principal,” including return received as rent from property; interest on money lent; corporate distributions (discussed in further detail below); accrued income on bonds (discussed in further detail below); receipts from principal used in a business (discussed in further detail below); receipts from the disposition of natural resources (not discussed as not applicable); receipts from other principal subject to depletion (discussed in further detail below); and receipts from the disposition of underproductive property (discussed in further detail below).

- EPTL §11-2.1(b)(2): defines principal as “property, disposed of in trust, the income from which is payable to or to be accumulated for an income beneficiary and the title to which is ultimately to vest in the person entitled to the future estate,” and includes consideration received on the sale or transfer of principal, on the repayment of a loan or as a refund, replacement or change in the form of principal; proceeds resulting from eminent domain; insurance proceeds other than proceeds from an income beneficiary’s separate interest; stock dividends; receipts from bonds; royalties; receipts from principal subject to depletion; any profit resulting from any change in the form of principal; and receipts from the disposition of underproductive property.

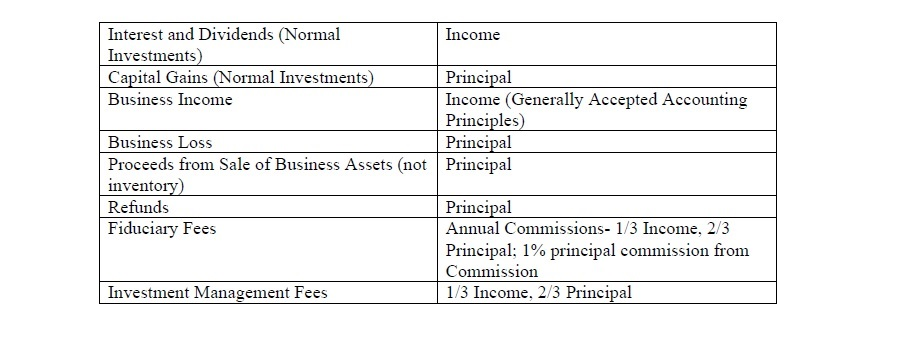

A summary of what constitutes income versus principal under the Principal and Income Act follows:

Determining Your Client’s Planning Needs

Before recommending the use of a revocable or an irrevocable trust, it is important to have a sense of whether the objectives of a client warrant creating a trust. The following may assist in the analysis of whether an irrevocable trust will be useful for the client:

• The intended beneficiaries do not have investment experience, knowledge, skills, or desire to gain the experience, knowledge or skills.

• The client wants another person or an institution to decide who will be a beneficiary and what a beneficiary is to receive.

• The client wants to shift an income tax burden from himself or herself to a trust or another party.

• The client wants to plan for Medicaid eligibility.

• The client wants to control when and how a beneficiary will receive income or principal from a gift.

• The client wishes to make a gift, but does not want the beneficiary/donee to have immediate access to the money or property.

• The client wishes to make a gift, but wants to retain the income from the money or property for a period of time.

• The client wants to skip one or more generations for purposes of reducing transfer taxes on property as it passes from generation to generation.

• The client wants to avoid the capital gain tax on assets that have a low basis.

• The client wants to maximize gift making, even to the extent of paying the income tax liability on the gifts.

• The client wants to divest him/herself of life insurance but wishes to indirectly control the use of the policy's cash value and policy proceeds on death.

Outright Gifts

Before a discussion involving the drafting of trusts, lifetime gifting must be considered. Lifetime gifts offer clients important savings for both estate and income tax purposes and remain one of the most important tools in estate planning. An outright gift is most appropriate when the donor wants the donee to have maximum freedom in owning and controlling the property.

Outright gifts shift the taxability of income and save estate taxes. Outright gifts may also include transfers of partial interests (such as legal life estates, remainders and other present and future interests). An outright gift is most appropriate when the donor wants the donee to have maximum freedom in owning and controlling the property.

Section 2503 of the Internal Revenue Code (the “Code”) allows an exclusion from taxable gifts for present interests given to each donee each year up to specified amount. The current annual exclusion is $14,000. The annual exclusion is tied to inflation, but may only be increased in increments of $1,000.

The annual gift tax exclusion is allowed only for a gift of a present interest (an “unrestrictive right to the immediate use, possession, or enjoyment of property or the income from property”). Future interests (reversions, remainders, and other interests or estates, whether vested or contingent, which are limited to commence in use, possession, or enjoyment at some future time) do not qualify for the gift tax annual exclusion. Gifts of future interests must be reported at their full value, and the annual exclusion is barred.

Revocable Trusts

The Revocable or Living Trust is currently very popular among elderly clients and their attorneys. Many clients believe that the Revocable Trust will work to reduce or eliminate estate tax. Others are under the impression that the Revocable Trust will protect assets in the case of nursing home placement. Still others think that if they have a Revocable Trust, there is no need for them to also have a Will. It is important that the drafting attorney be able to correct each of the above misconceptions when advising clients and particularly when reviewing existing

Revocable Trusts prepared by other attorneys.

The advantages of using a Revocable Trust often cited by estate planning attorneys include:

• Avoiding probate;

• Maintaining privacy;

• Avoiding ancillary probate;

• Avoiding Will contests;

• Quick disposition; and

• Asset management.

Avoiding Probate: Many attorneys market (and clients believe) that one of the most important concerns in estate planning is to avoid probate. There may be times when a particular client has already experienced the probate process with the estate of a close family member and not had a good experience. There is time, expense and judicial impediments that can arise during the probate of a Will (a subject for another seminar); however, in many New York counties outside New York City, probate is not the horror that is commonly portrayed. An attorney with experience in a particular county will know the intricacies of that particular court. Where waivers of citation may be easily obtained from all beneficiaries, probate is not time consuming or expensive. Further, a client may want court supervision if the client anticipates a fight.

Privacy: There is no requirement that a person be rich and famous to want privacy.

Many clients do not want their estates made public. They may not want the public to know which heir receives what property. As a private contract, an inter vivos Revocable Trust is not a public document and is therefore not subject to inspection by the courts or the general public.

However, if the Revocable Trust is not fully funded and a pour over Will is used to transfer any remaining assets into the Revocable Trust at death, the Court will frequently require that the

Revocable Trust be filed with the Will in the probate proceeding, thereby removing the “privacy” advantage.

No Ancillary Probate: In addition to determining whether an estate is subject to the probate process, a similar determination must be made in each state where the decedent owns property. Where a Revocable Trust holds real property located in a jurisdiction different from where the decedent resides, title to the property continues to be held by the trust upon the grantor’s death. Therefore, there will be no need for probate in another state (ancillary probate).

For example, if the grantor’s primary residence is New York, but the grantor also owns a home in Massachusetts, the grantor may transfer the Massachusetts real estate to a Revocable Trust, thereby avoiding probate in both states.

Avoid Contests: Although a trust instrument can be subject to challenge, it is more difficult to challenge an agreement that has been in effect during a grantor’s lifetime. It is important to note that a Revocable Trust is not sufficient to defeat a right of election of the decedent’s surviving spouse. Avoiding contests is particularly important when the client is gay and wants his or her assets to be distributed to his or her domestic partner. If the client’s only surviving family includes non-approving family members, these family members may attempt to challenge the Will as distributees. Remember that during the probate of a Will, the decedent’s distributees must either sign or Waiver of Citation or be served with a citation, thereby opening the door for objections.

Quick Disposition: The Revocable Trust provisions may provide for disposition to named beneficiaries on the death of the grantor, or in some other manner. Depending on the complexity of the decedent’s estate, assets passing pursuant to the Revocable Trust may save several months. This becomes important where a family business is involved or where a constant flow of income is crucial.

Asset Management: With respect to Revocable Trusts, if the grantor is also named as Trustee, the Revocable Trust is his or her “alter ego” and he or she retains complete control over the trust and its assets. This allows the grantor to manage the assets and make any necessary changes if needed to accomplish his or her goals. New York State has abolished the merger doctrine, allowing the grantor to act as sole Trustee, thereby removing the need for a co-Trustee.

The Revocable Trust may also provide trustee succession provisions that do not require court involvement, providing ease in the transfer of fiduciary duty upon the grantor’s incapacity or death.

Professional Management: The grantor/trustee may retain a financial professional to manage assets in the trust for the grantor’s benefit. This may be important where the grantor lacks expertise or interest in managing trust assets such as real estate, stock funds, or even a valuable art collection. The grantor/trustee may also change advisors if necessary.

Incapacity: Although an attorney-in-fact/agent named pursuant to a valid, durable power of attorney may manage assets on behalf of an incapacitated person, a Revocable Trust may provide the Trustee with much greater flexibility, control and authority in managing the trust assets. Many attorneys-in-fact/agents have experienced problems with having various financial institutions honor a power of attorney document. Although the banks or other financial institutions are most often unjustified in refusing to recognize the power of attorney, it is a pervasive problem within the community. Conversely most institutions will recognize the authority of the Trustee. However, they may require that a full copy of the trust instrument be provided.

Realistically, a Revocable Trust should be considered for New York clients in the following cases:

• The client owns real estate in a foreign jurisdiction.

• The client has a domestic partner who the client wants to inherit.

• The client is involved in a non-traditional family relationship (i.e. second marriage or no marriage).

• The client wishes to keep something private.

• The client may move to a state where probate is more complex.

• The client may acquire real estate, such as a vacation home or a retirement home, in another state.

Types of Irrevocable Trusts and Purposes They Serve

Irrevocable trusts are used for a myriad of purposes, although they are mostly tax related. Many times a single type of irrevocable trust can be used for a variety of different tax purposes. For example, an irrevocable life insurance trust with Crummey withdrawal rights is used to make gifts that qualify for the annual exclusion and exclude life insurance from the grantor's estate.

Inter vivos irrevocable trusts include the following:

• Basic irrevocable trusts;

• Crummey withdrawal or demand;

• Generation-skipping and dynasty trusts; and

• Specialized trusts, such as equipment leasing trusts, educational trusts, and incentive trusts.

Grantor trusts are those trusts whose income is taxable to the grantor under Sections 671 through 679 of the Code. A Revocable Trust is a grantor trust because of its revocability by the grantor. An irrevocable trust is a grantor trust if grantor has a reversionary interest in the trust assets or has retained certain powers (“strings”) over the trust.

On occasion, an irrevocable inter vivos trust is made a “defective grantor trust” on purpose; that is, the trust is drafted with certain retained powers (“strings”) by the grantor that cause the trust's income to be taxed to the grantor but that do not cause inclusion of the trust assets in the taxable estate of the grantor. Since the Code requires the grantor to recognize the trust's income and pay the income taxes on that income, the trust's beneficiaries receive the income intact. The taxes paid by the grantor are, in essence, an additional gift to the beneficiaries. However, the gift is not subject to federal gift tax, because the income tax payments are not voluntary but are required by law.

Grantor trusts include annuity or unitrusts that allow the grantor to retain an income or unitrust interest in the trust assets for a period of years before the assets vest in the name of the other beneficiaries. Contributions to these grantor-retained annuity and unitrusts (GRITs, GRATs and GRUTs) result in a gift to the beneficiaries equal to the value of the contribution to the trust less the value of the grantor's retained interest for the trust term. These trusts allow the grantor to divest himself or herself of the future appreciation without giving up the income immediately.

The value of the gift to the beneficiaries is discounted by the actuarial value of the grantor's retained interest. There are special trusts that allow this same treatment if the trust is funded with the grantor's residence or a vacation home (qualified personal residence trust or QPRTs).

Grantor trusts include the following types of trusts:

• Lifetime QTIP (Qualified Terminable Interest Property) trusts;

• Grantor-retained annuity trusts (GRATs) and unitrusts (GRUTs);

• Grantor-retained income trusts (GRITs) for nonfamily members;

• Qualified personal residence trusts and personal residence trusts (QPRTs); and

• Intention-Defective ally Grantor “defective” trusts.

Before recommending the use of an irrevocable trust, it is important to have a sense of whether the objectives of a client warrant creating an irrevocable trust. The following may assist in the analysis of whether an irrevocable trust will be useful for the client:

• The intended beneficiaries do not have investment experience, knowledge, skills, or desire to gain the experience, knowledge or skills.

• The client wants another person or an institution to decide who will be a beneficiary and what a beneficiary is to receive.

• The client wants to shift an income tax burden from himself or herself to a trust or another party.

• The client wants to plan for Medicaid eligibility.

• The client wants to control when and how a beneficiary will receive income or principal from a gift.

• The client wishes to make a gift, but does not want the beneficiary/donee to have

immediate access to the money or property.

• The client wishes to make a gift, but wants to retain the income from the money or property for a period of time.

• The client wants to skip one or more generations for purposes of reducing transfer taxes on property as it passes from generation to generation.

• The client wants to avoid the capital gain tax on assets that have a low basis.

• The client wants to maximize gift making, even to the extent of paying the income tax liability on the gifts.

• The client wants to divest himself or herself of life insurance (subject to federal estate tax) but wishes to indirectly control the use of the policy's cash value and policy proceeds on death.

Insurance Trusts

An irrevocable life insurance trust can remove the policy proceeds from the estates of both the insured and the surviving spouse, while making the proceeds fully available to meet the needs of the surviving spouse and the insured's estate.

An irrevocable gift of a life insurance policy in a trust is made by the irrevocable assignment of all of the incidents of ownership in one or more life insurance policies to the trustee of an irrevocable life insurance trust. An irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT) may be either funded or unfunded. A funded trust contains assets other than life insurance policies, and these assets are often held to produce sufficient income to pay the insurance premiums. An unfunded ILIT contains only life insurance policies. The insured typically pays premiums on policies held by an unfunded ILIT, either by direct payments to the insurer or by annual gifts to the trustee in amounts sufficient for the trustee to pay the premiums.

The dispositive provisions of a single policy (insurance only insuring one person) are normally designed so as to make the proceeds available to the surviving spouse, while still preventing inclusion of the proceeds in the surviving spouse's estate. The trust for the surviving spouse must not give the surviving spouse any powers that would constitute a general power of appointment or the proceeds will be included in the surviving spouse's gross estate.

Advantages in making life insurance gifts through an ILIT rather than making them outright or through a Revocable Trust include:

• An ILIT can remove the insurance proceeds from both the insured's and the surviving spouse's gross estates while making those proceeds largely available to the surviving spouse.

• A gift of an insurance policy to an ILIT gives the insured more control over the policy than would an outright policy gift. The use of a trust ensures that the proceeds will be used for the intended purpose.

• A well-drafted ILIT can sometimes still afford the insured the indirect benefit from the policy cash values. This can be achieved by giving the insured's spouse the right to invade principal subject to an ascertainable standard for, his or her health, education, support, and maintenance, determined without taking into account other available resources.

Disadvantages in making gifts of life insurance policies in trust rather than making them outright include:

• The cost of preparing the trust agreement. If the trust is unfunded, no annual tax returns will be required, because the trust will have no income. However, books of account should still be kept, and the trust should have a tax identification number.

• Most trustees charge a fee for their management services. While these fees may be nominal during the insured's lifetime (when the trust has little or no assets), they can be substantial after the insured's death.

• ILITs usually require special provisions in order for gifts to the trust to qualify for the gift tax annual exclusion (Crummey withdrawl or demand rights) and for the insured to retain the income tax deduction for interest paid on policy loans.

• If the insured dies within three years of transferring the policies to the trust, the policies will be included in the insured's gross estate. One of the key objectives with any ILIT is removing the policy proceeds from the insured's gross estate at the least possible gift tax cost and, if possible, without diminishing the available gift tax exemption.

A gift of an insurance policy in trust is a nonqualifying gift of a future interest, absent a special trust provision creating a present interest in one or more beneficiaries. The only practical way to obtain the annual exclusion for a gift of a life insurance policy in trust is through Crummey demand power or withdrawal right.

A Crummey withdrawal right creates a present interest despite the fact that it may be available only for a short time. The demand period must be long enough to give the beneficiary a meaningful interest in the property given to the trust. The beneficiary must be given a realistic opportunity to actually withdraw the grantor's contribution. Whether the gift is cash or insurance policies, the IRS has repeatedly stated that a withdrawal power does not create a present interest unless the beneficiary (if an adult) is aware of its existence and is aware of any gift against which it may be exercised. A trustee must notify any adult demand power holders of the right to make a withdrawal, and of each gift to which the withdrawal relates. The IRS has not publicly addressed the question of notifying minor beneficiaries, but it is sound practice to give a similar notice to the person who would be allowed to exercise the demand power on the minor's behalf (usually the minor's parent or legal guardian).

Testamentary, Credit Shelter or Family Trust

The federal estate tax and gift tax have been re-unified with an exemption equivalent of $5.34 Million in 2014 with indexing for inflation..When drafting an estate plan for tax planning clients, the goal is to use the estate tax exemption of each spouse and, at the same time, ensure that the assets comprising the estate tax exemption of the first spouse to die will be available to the surviving spouse. A client with $1.5 Million to $3 Million in assets usually wishes to defer estate tax on any amount in excess of the exemption until the death of the surviving spouse. A client with more than $3 Million in assets may choose to pay some estate tax on the first death in order to avoid bracket creep on the second death.

The estate tax exemption of the first spouse to die can be used to establish a family trust (also known as a credit shelter trust or bypass trust) for the benefit of the surviving spouse and descendants or to make gifts to the children. In very large estates, a distribution to children is often sensible. In more modest estates, the surviving spouse may need the income and access to principal. The concept is that the assets in the assets passing to the family trust are includable in the estate of the first spouse to die. As long as the surviving spouse does not have a general power of appointment over the assets held in the family trust, those assets (and the appreciation on those assets) will escape tax on the second death. The spouse's right to invade principal must be limited to a five and five power and an ascertainable standard.

The residuary estate of the first spouse to die is divided between the marital gift (or marital trust) and the family trust, by one of 2 methods: (1) fractional-share method or pecuniary-share method. Under the fractional-share method, the residuary estate is divided by fractions (or percentages) as determined by the value as finally determined for federal estate tax purposes. The appreciation or depreciation between the date of death (or six months later) and the date the trusts are funded are shared proportionally. There is no income tax consequence on the funding of the fractional shares.

Under the pecuniary-share method, either the marital gift (or marital trust) or the allocation to the family trust is defined as a pecuniary amount, leaving the residue for the other. A pecuniary share is generally determined on the basis of the estate tax return values but is funded with date-of-funding values. Appreciation or depreciation is placed in the non-pecuniary residuary share. On funding the pecuniary share with assets of the estate, there is an income tax consequence based on the difference between the value of the assets at the time of distribution and the estate tax values. Selection of the appropriate formula is particularly important when the beneficiaries of the two shares are different, such as in a second marriage.

The family trust terms may benefit the surviving spouse alone or may be drafted to benefit both the surviving spouse and the decedent’s descendants during the surviving spouse’s lifetime. Careful attention should be given when the surviving spouse and decedent spouse have different children. For example, if Husband has 2 children by deceased First Wife and Second Wife has 3 children, Husband’s Will may include a family trust for the sole benefit of Second Wife or for the benefit of Second Wife and his descendants. The Will must include a provision as to whose needs should be considered first when making discretionary distributions from the family trust (Second Wife or Husband’s Descendants?).

Standard terms of a family trust typically include:

• The surviving spouse is co-Trustee;

• The surviving spouse (and descendants) may receive discretionary income and principal for health, support or education (ascertainable standard).

• The surviving spouse (and descendants) may receive discretionary income and principal for any reason, within the discretion of an Independent Trustee.

• The surviving spouse may withdraw up to the greater of $5,000 or 5% of the family trust assets annually (5&5 power- best to limit this power to one day or one week per year to avoid inclusion of the power in the estate of the surviving spouse).

• During his or her lifetime, the surviving spouse has the limited power to appoint principal among the decedent spouse’s descendants; provided that the power is not used to satisfy the legal obligations of the surviving spouse.

• At death, the surviving spouse has the limited power to appoint principal among the decedent spouse’s descendants. In some cases, the client may not be willing to establish a Will with the marital and family trusts. In these cases, a disclaimer Will may be used. Under a disclaimer trust, the Will of the first spouse to die leaves the entire estate outright to the surviving spouse. Then, the surviving spouse is given the right to disclaim (or renounce) all or part of the gift. The Will then establishes a trust similar to a family trust. If the surviving spouse disclaims, the disclaimed assets go to the disclaimer trust (or family trust), which uses all or part of the estate tax exemption of the first spouse to die. However, there are several disadvantages to a disclaimer trust. A disclaimer trust is not practical if the residuary beneficiaries of the trust are not the beneficiaries of the surviving spouse. The disclaimer must be made within 9 months of the death of the first spouse in writing and filed with the applicable Surrogate’s Court in accordance with New York Estates, Powers and Trusts Law §2-1.11. It is easy for a surviving spouse to violate the disclaimer rules by using the assets before a qualified disclaimer is made. Finally, a surviving spouse may not be given a limited power of appointment over the disclaimer trust assets.

One method of incorporating flexibility in a Will is to provide that the entire residuary estate is left in a trust that qualifies as a QTIP trust and authorize the Executor to elect whether to qualify any portion of the trust for the marital deduction. With this approach, the Executor can decide how much of the trust to qualify for the marital deduction in order to use the decedent's applicable exemption amount and postpone the payment of estate tax until the death of the surviving spouse.

Marital Trusts

One method of incorporating flexibility in a Will is to provide that the entire residuary estate is left in a trust that qualifies as a QTIP trust and authorize the Executor to elect whether to qualify any portion of the trust for the marital deduction. With this approach, the Executor can decide how much of the trust to qualify for the marital deduction in order to use the decedent's applicable exemption amount and postpone the payment of estate tax until the death of the surviving spouse.

The pecuniary bequest rule is confined to marital bequests and trust transfers of a dollar amount (so-called pecuniary formula and nonformula bequests and trust transfers) where the will or trust agreement: (1) permits or requires the executor or trustee to satisfy the bequest or transfer with estate assets “in kind” selected by the executor or trustee, and (2) the assets distributed in kind are to be valued at their value as finally determined for federal estate tax purposes.

The pecuniary bequest rule specifically allows the marital deduction in full if the discretion of the executor or trustee is limited so that he has a fiduciary duty under state law, or the provisions (expressed or implied ) of the Will or trust agreement, which requires the fiduciary to do only one (but not both) of the following: (1) satisfy the bequest or transfer by distributing assets, including cash, with an aggregate fair market value at the date or dates of distribution at least equal to the amount of the pecuniary bequest or transfer, or (2) distribute assets including cash, “fairly representative” of appreciation or depreciation in the value of all property available for distribution in satisfaction of the bequest or transfer.

The marital deduction for the pecuniary bequest or transfer is entirely disallowed under the pecuniary bequest rule where property available for distribution might fluctuate in value, if it is not clear from the Will or trust instrument, or state law, that the fiduciary's discretion as to payment of the bequest or transfer is limited so as to treat the surviving spouse on the same basis as other distributees or to give the surviving spouse the equivalent of the estate tax value of the surviving spouse’s bequest. The bequest might also be disallowed on the ground that the fiduciary has a “power to appoint” part of the marital bequest to persons other than the surviving spouse by reason of the fiduciary’s authority to satisfy it in kind at estate tax values with depreciated property.

If the Will provides for distribution in accordance with requirement (1) above, the fact that at the time of final distribution the aggregate value of available assets has so depreciated that it is impossible to transfer assets to the surviving spouse having an aggregate value equal to the amount of the bequest would not bar the marital deduction for the full amount of the bequest.

In a distribution under (2) above, the property available for distribution includes property which can be used by the executor to satisfy the marital deduction bequest during the entire period of estate administration up to the time the bequest is satisfied in full. And it would include capital gains realized by the estate on the sale of estate assets to pay debts and taxes.

Note that IRS's requirement for allowance of the deduction is not satisfied unless it is clear that the fiduciary's discretion is limited to only one of the qualifying distributions exclusive of the other. Discretion to use either one of the two types of distribution (or a mixture of them) does not qualify.

Typical marital trust provisions include:

• The surviving spouse is a co-Trustee;

• The surviving spouse receives the income at least annually

• The surviving spouse may receive discretionary principal for health, support or education (ascertainable standard);

• The surviving spouse may receive discretionary principal for any reason, within the discretion of an Individual Trustee;

• The surviving spouse may withdraw up to the greater of $5,000 or 5% of the marital trust assets annually.

Generation Skipping Exempt and Non-Exempt Trusts/Dynasty Trusts

The generation-skipping transfer tax (GSTT) is imposed at a flat rate equal to the highest federal transfer tax rate in existence at the time of the transfer on three types of generationskipping transfers (GSTs). GSTs generally occur when a transferor transfers an interest in property to a “skip person.” A “skip person” is a person who is assigned to a generation that is at least two or more generations younger than the transferor's generation. All other transferees are non-skip persons. Direct skips, taxable distributions and taxable terminations are the three different types of GSTs.

A “direct skip” is a gift during life or a transfer at death from a transferor directly to a skip person (a gift from grandparent to grandchild is a direct skip, unless grandchild's parent who is grandparent's child is dead at the time of the transfer). A direct skip is subject to estate or gift tax and to GSTT. A direct skip gift to a trust is taxed like a direct skip gift to an individual.

A “taxable distribution” is a distribution of either income or principal from a trust to a skip person. If grandparent creates a trust for the lifetime benefit of children (non-skip persons) and more remote descendants (skip persons), any distribution made from the trust to any remote descendant is a “taxable distribution.”

A “taxable termination” is the termination of the interest of a beneficiary in a trust if, immediately after the termination, no non-skip person has a present beneficial interest in the trust and at least one skip person is or could be a beneficiary of the trust. If grandparent creates a trust for the lifetime benefit of children and more remote descendants, the death of the last of the children to die is a taxable termination because no more beneficiaries exist assigned to the first generation below grandparent, and beneficiaries remain who are skip persons.

Each individual transferor has a $5.34 Million GSTT exemption (tied to the estate tax exemption) that can be allocated against any transfer that is, or later may be, subject to GSTT. The GSTT is imposed on a taxable event based on the amount of GSTT exemption allocated to the trust or direct skip. If the transferor allocates GSTT exemption to a direct skip or trust, the GSTT will be reduced or eliminated through a mechanism called the “inclusion ratio.” The “inclusion ratio” is the percentage of the outright transfer that exceeds the amount of GSTT exemption allocated. The inclusion ratio is defined as a formula of one minus the fraction of the transfer sheltered from tax by the GSTT exemption allocated.

An inclusion ratio of one means that no GSTT exemption was allocated and the entire transfer is subject to the GSTT. An inclusion ratio of zero means that the transfer can be thought of as if none of the transfer is taxable. An inclusion ratio of some other fraction means that the transfer can be thought of as if a fractional share of the transfer is taxable. The inclusion ratio affects only the tax rate and not the amount of the transfer subject to the GSTT.

Ideally, a trust with a zero inclusion ratio should be capable of lasting as long as state law permits under the applicable Rule Against Perpetuities. New York maintains the common-law Rule Against Perpetuities, in which all trust interests are invalid unless they must vest, within a life in being plus twenty-one years.

Generation skipping transfer tax exempt trusts (“Exempt Trusts” or “dynasty trusts”) should be drafted to last as long as permitted under applicable state law. This often means selecting a large class of measuring lives on which to base the maximum term of the trust. A common approach is to provide that the trust interests must all vest in absolute ownership within twenty-one years from the death of the last of the descendants of the parents of the donor and the donor’s spouse alive when the trust is created.

Even if the GSTT no longer applies as a result of the one-year repeal under EGTRRA, Exempt Trusts and dynasty trusts that run for the entire term of the Rule Against Perpetuities will remain valuable for estate planning purposes as these trusts would provide creditor and divorce protection. The trust should be drafted flexibly and give the trustee broad distribution powers—including the ability to distribute into further trust—and could give limited powers of appointment to beneficiaries. For added flexibility, a charity could be included as a beneficiary.

From a tax perspective, an Exempt Trust should be used to benefit skip persons of as many generations as possible. Any distribution to a non-skip person is, at least for transfer tax purposes, a waste of GSTT exemption. The higher the generation of the non-skip person, the greater the waste. Distribution of exempt assets to non-skip persons puts property distributable to skip persons without additional transfer tax back into the transfer tax system at a higher generation level than necessary.

Rather than making outright distributions of the non-exempt share of the beneficiaries’ inheritance, generation-skipping transfer tax non-exempt trusts (“Non-Exempt Trusts”) offer the benefits of creditor and divorce protection. The Non-Exempt Trust should be structured to minimize the overall gift, estate and generation-skipping transfer tax.

In drafting Non-Exempt Trusts, the decision must be made whether (and how) to incur a gift tax or an estate tax rather than GSTT. There are certain benefits available for transfers subject to gift or estate tax that are not available for transfers subject to GSTT. As such, it may be advantageous to convert what would be a GST into a transfer subject to gift or estate tax.

Advantages to the estate and gift tax that are not available to GSTT include:

• The estate tax and gift tax exemption equivalents and use of the lower-rate brackets are available for both estate and gift taxes, but not for GSTT.

• The estate tax exemption and lower rate brackets can be doubled if the child is married, as the child can also use the estate and gift tax marital deductions to take advantage of any unused estate tax exemption and the possible lower rate bracket of the child's spouse.

• Paying an estate tax may be better than paying a GSTT because of the estate tax credit under Section 2013 for property previously taxed. If property is included in the estate of a child who dies within ten years of the date of the death of the transferor, then, depending on the reason the property was included in the child's estate, all or part of the estate taxes already paid by the transferor's estate on the property should be creditable against the child's estate tax liability.

• The recipients of property subject to estate tax receive, in general, a basis in the assets for income tax purposes that is equal to the fair market value of the assets as of the date of the decedent's death. In contrast, the GSTT basis adjustments for transfers at death are available only for taxable terminations.

• The gift tax may be more advantageous than the GSTT because of the gift tax annual exclusion. As with the unified credit and lower tax brackets, this can also be enhanced by gift splitting under Section 2513 or by the use of the gift tax marital deduction, to enable the use of the annual exclusions for gifts by the child's spouse.

• The gift tax may be less expensive than the GSTT on a taxable termination or a taxable distribution. The gift tax is imposed solely on the value of the assets received by the recipient. In contrast, the GSTT on a taxable termination or taxable distribution is imposed on the entire amount available to make the transfer and to pay the tax. Thus, the gift tax is “tax exclusive” (if the donor lives more than three years after the gift), while the estate tax and GSTT on such taxable events are “tax inclusive.” The GSTT may be preferred to the estate or gift tax in the following situations:

• The GSTT can be better than the estate or gift tax because of the possibility of double skips. If a GST skips several generations, it avoids estate and gift tax at each generation. The proper comparison in these cases may be between a GSTT and two or three estate or gift taxes.

• No GSTT is imposed on transfers from beneficiaries who are in the same or a higher generation. For example, a trust could benefit the transferor's parents, then siblings, then children, and finally grandchildren. While outright successive transfers to each person would result in estate or gift tax, no GSTT would be imposed until such time when the trust was solely for the benefit of the grandchildren.

• The GSTT on a direct skip has a lower effective tax rate than the estate tax. The GSTT in such cases is tax exclusive, while the estate tax is tax inclusive.

• The GSTT may be superior to the payment of a gift tax with respect to gifts of certain corporate shares or partnership interests. According to the Preamble to the proposed Chapter 14 regulations, the special valuation rules of Section 2701, relating to preferred interests in certain corporations and partnerships, do not apply for purposes of valuing GSTs.

There are several ways to attract an estate or gift tax instead of a GSTT. Each has both advantages and disadvantages in certain situations. The simplest way to obtain a gift tax instead of a GSTT is by making outright gifts to a non-skip person. Similarly, an estate tax may be substituted for the GSTT by leaving property outright to the transferor's children or other nonskip persons (such as children of a predeceased child). Also, an individual could give relatively small amounts to a non-skip person with the nonbinding request that the amounts be given to specific individuals who are skip persons relative to the transferor but not to the non-skip person.

A result similar to outright distribution to a non-skip person can be achieved when property is left in trust, if the trust benefits both skip persons and non-skip persons, and if the trustee is authorized to make liberal distributions to non-skip persons. Of course, the trustee must be aware of the family structure and be willing to make distributions to non-skip persons who are in a position to make further gifts to skip persons.

One of the most useful tools for converting a GSTT liability into an estate or gift tax liability is granting to a non-skip person a general power of appointment over property or a portion of the property. For estate and gift tax purposes, trust assets that are subject to the power of appointment are generally treated as if owned by the holder of the power. Therefore, the exercise or lapse of an inter vivos power is a taxable gift of the subject property by the holder of the power to the appointee or taker in default. Similarly, if the holder dies while possessing the general power of appointment, the value of the subject property is included in his or her gross estate for estate tax purposes.

An automatic formula may be advisable in trusts (other than irrevocable inter vivos trusts that are not includable in the grantor's estate). Trust assets that are subject to the general power of appointment are generally treated as if owned by the holder of the power for estate and gift tax purposes. Therefore, under Code §2514, the exercise or lapse of an inter vivos general power is a taxable gift of the subject property by the holder of the power to the appointee or taker in default or appointee. Similarly, if the holder dies while possessing the general power of appointment, the value of the subject property is included in his or her gross estate for estate tax purposes under Code §2041.

The fundamental problem with giving a beneficiary a general power of appointment is that the question of whether the GSTT or the estate tax will be more advantageous cannot be known with certainty until a later time. For example, if a child is not survived by descendants, and the property passes to the child's siblings, no GSTT will be imposed, and exposing the trust to estate taxes at the child's death creates an unnecessary tax. If the property passes to skip persons, the estate tax is likely to be more advantageous. If a general power of appointment is created by a third party after the death of the transferor, the powerholder's estate is not eligible for the credit for tax on prior transfers of Section 2013 that otherwise might apply, if the power had been created by the grantor and the holder dies within ten years of the grantor's death.

A transferor who is reluctant to allow a non-skip person to have the power to appoint trust property to the skip person personally or the skip person's creditors or to the creditors of the skip person's estate may wish to condition the exercise of the power on the consent of a nonadverse person, such as an independent trustee. Both Code §2041 and §2514 treat a power of appointment as a general one, even if it is exercisable only in conjunction with an independent party who does not have a substantial adverse interest.

One variation on the grant of a general power of appointment is the grant to a trustee of the power to grant a general power of appointment to a non-skip person (or the power to expand a special power of appointment held by a non-skip person into a general power). The fundamental problem with giving a beneficiary a general power of appointment is that the question of whether the GSTT or the estate tax will be more advantageous cannot be known for sure until a later time. For example, if a child is not survived by descendants, and the property passes to the child's siblings, no GSTT will be imposed. Exposing the trust property to estate taxes at the child's death thus creates an unnecessary tax. If the property passes to skip persons, the estate tax is likely to be more advantageous. If a general power of appointment is created by a third party after the death of the transferor, the powerholder's estate is not eligible for the credit for tax on prior transfers that otherwise might apply if the power had been created by the grantor, and if the holder dies within ten years of the grantor's death.

If a trustee is given the power to grant a general power of appointment to a non-skip person or to convert a limited power of appointment into a general power of appointment, it may be advisable to give the trustee the power either to rescind the grant or to convert the power back again. The power to convert a limited power back to a general power gives the trustee the ability to protect the trust assets from estate tax in the event that the GSTT is repealed, its rate is reduced, or for any other reason the GSTT becomes more desirable than the estate tax.

Incentive Trusts

Incentive trusts are trusts that seek to affect a beneficiary's behavior by conditioning a benefit. The use of incentive provisions in trusts for children and more remote descendants has become a popular topic within the estate planning community.

Incentive trust provisions can be designed to encourage particular achievements (graduating from college or trade school), discourage certain activities or associations (dating a certain individual), address specific behavioral problems (substance abuse), or reflect general goals (productive behavior). Trusts can use financial incentives (distributions of income or principal) or status incentives (appointment to a position of authority over the trust or property owned by the trust) as incentives to encourage the desired behavior.

Rather than spelling out all of the grantor’s “rules” for distribution, the grantor may implement precatory language into the trust providing the trustee with his or her general philosophy regarding discretionary distributions from the trust. The primary advantage of giving the trustee broad discretion is that the trustee will be well positioned to react to changes in the beneficiary's personal circumstances over time. The primary disadvantage is that the more discretion given the trustee, the greater the grantor’s risk that the trustee will administer the trust inconsistently with the grantor's intent.

The question of who will serve as trustee of an incentive trust is important and also raises the issue of how to protect the trustee. Broad powers granted to the trustee could cause the property to be taxed in the trustee's estate or in the estate of the beneficiary if the beneficiary has the right to change the trustee. The risk that the property will be taxed in the estate of the trustee can be eliminated by prohibiting the trustee from making distributions to himself or herself, and, if the trustee is a parent of the beneficiary, precluding the trustee from making distributions to the beneficiary that would satisfy the parent-trustee's obligation of support. The risk of inclusion in a beneficiary's estate can be eliminated if the trust instrument does not allow a beneficiary to appoint himself or herself or a related or subordinate party trustee.

A common incentive provision is one that defers the date that a child will come into possession of the child's full inheritance to an age when the parent hopes that the child will have matured or will receive installments over several years. The advantage is that these provisions are simple for the trustee to administer and for the beneficiary to understand. In addition, installments allow the beneficiary to learn about managing property while protecting the remaining inheritance.

Trusts may also include gainful employment provisions to create objective criteria for the trustee to follow in making distributions. Absent any discretion given to the trustee, a child who engages in an activity not specifically noted as an exception to gainful employment may find himself or herself effectively disinherited even though the trustee firmly believes the parent would have supported the child's actions.

Incentive provisions may also direct the withholding of distributions for a child who is under the influence of a cult or has a drug or gambling problem. A provision that permits distributions to a child to assist in the acquisition of a business or profession may be viewed as an incentive. If a trust is authorized to invest in a business enterprise established by a beneficiary, the trust should contain language that separately authorizes closely held businesses as appropriate trust investments, directs who should make management decisions for the family business, and exonerates the trustee from liability for such an investment.

Another common feature of incentive trusts is the inclusion of provisions that make it clear that the trustee is entitled to request information from a beneficiary. Although a grant of very broad discretion to the trustee, in practice, probably would permit the trustee to refuse to make a distribution unless particular information is provided, the request for information will be legitimized if there is a broad grant of authority for the trustee to request information.

Education Trusts

Advantages of Code §2503 Trust:

- Asset protection from future creditors

- Federal income tax consequences flow through to beneficiaries to the extent trust income is distributed to beneficiaries.

- No contribution limits.

- Contributions not limited to cash.

Code §2503(c) Trusts

If the trust meets these requirements, entire value of property transferred is eligible for §2503(b) annual exclusion. §2503(c) provides special exclusion for gifts benefiting person under 21 years old that would normally be a future interest as long as:

- Minority Interest: Principal & income must be available for distribution while donee is under 21.

- Termination at 21: If donee survives to age 21, all accumulated income & principal must be distributed to donee at age 21.

- Distribution at Death of Donee: If donee dies before age 21, all income & principal must be paid either to donee’s estate or to donee’s appointee pursuant to a general power of appointment.

- Income & principal may be expended for donee before donee turns 21.

- Trustee must be given discretion to determine amounts & purposes for distributions… but NO substantial restrictions on discretion.

- Sprinkle powers do NOT satisfy §2503(c); must establish separate shares for each beneficiary (each share qualifies as a separate trust & qualifies for §2503(c) exclusion. No substantial restriction is Trustee has at least as much discretion as that of a guardian under local law. If substantial restriction, minority interest requirement is not met:

- “For accident, illness or emergency” = Substantial Restriction

- “Support, care, education, comfort & welfare” ≠ Substantial Restriction

- Reg §25.2503-4(b)(2): a gift will not be a future interest merely because donee MAY ELECT to extend the trust term.

- Rev. Rul. 74-43: §2503(c) exclusion if beneficiary, upon reaching age 21, has EITHER:

- Continuing right to compel distribution from trust, or

- Right during limited time period to compel distribution from trust by giving written notice & on failure of which trust will continue on its own terms.

- Payable to Donee’s Estate, or

- Pass Pursuant to a general power of appointment granted to donee.

- General Power of Appointment: the power to change the ultimate beneficiaries of the trust among the “Tainted Class” (the donee, the donee’s creditors, the donee’s estate or the creditors of donee’s estate).

Code §2503(b) Trusts

Qualifies for §2503(b) annual gift tax exclusion & need NOT terminate at beneficiary’s 21st birthday.

Involves only 1 beneficiary but 2 legal interests, each of which is for the beneficiary:

o Income Interest: Donee is given a life income interest. Trustee is given discretion to make principal distributions while donee is a minor.

o Remainder Interest

ADVANTAGES

o Income interest qualifies for §2503(b) exclusion.

o Need not end at any significant age.

DISADVANTAGES

o Annual income MUST be distributed to minor donee.

o Income interest must have ascertainable value (under-productive assets subject to challenge). §2503(b) exclusion only applies to income interest (present interest) and NOT to remainder interest (future interest). Income must be paid out “as soon as reasonably practical.” Annual income distributions have been held to suffice.

Supplemental Needs Trusts

There are two general types of supplemental needs trusts- first party and third party. A first party supplemental needs trust is established with an individual’s own assets, and is subject to payback to the State for services received by the individual during his or her lifetime. A third party supplemental needs trust is a trust established with another person’s assets, which is not subject to payback to the State for services received by the beneficiary during the beneficiary’s lifetime.

EPTL 7-1.12 governs supplemental needs trusts and provides sample language to be included in a supplemental needs trust. It is important to remember that the beneficiary of the trust must have a “severe and chronic or persistent disability” for the trust to qualify as a supplemental needs trust. Practitioners have attempted to established supplemental needs trusts for elderly surviving spouses as a way of protecting the deceased spouse’s assets from the surviving spouse’s long term care expenses that could otherwise be covered by Medicaid. Under the surviving spouse has a “sever and chronic or persistent disability,” simply being older will not qualify the trust as a supplemental needs trust.

Asset Protection (Medicaid) Trusts

A transfer to a trust may defer the gift tax and income tax consequences associated with outright transfers. A “Medicaid Trust” is an irrevocable trust that a grantor may establish which pays the grantor the income (interest and dividends) generated by the trust, but protects the trust assets (underlying trust principal) for designated beneficiaries. The grantor must take the income at least annually, and the grantor will report all income on the grantor’s personal income tax return. If the grantor enters a nursing home, the income must be used for the grantor’s care, but the underlying trust assets will be protected for the beneficiaries. Drafted properly, no gift tax will be associated with the transfer of assets to the trust, and, upon the grantor’s death, a “stepup” in basis is available (the individual receiving the assets at the grantor’s death receives a basis equal to the fair market value of the assets as of the grantor’s date of death).

In addition to the gift tax and income tax advantages of using a Medicaid Trust, there is the distinct advantage that the grantor will know where the trust assets are as opposed to making outright gifts to family members with the assumption that the gifts will not be spent until after the grantor’s death. Under New York State law, an irrevocable trust can be changed or terminated if all of the beneficiaries of the trust are competent adults and the grantor and the beneficiaries all agree to the change or termination in writing. As such, the use of a Medicaid Trust permits the grantor to change or terminate the irrevocable trust so long as the only beneficiaries are competent adults, and all agree to the change in writing.

The Medicaid Trust can also include a limited or special power of appointment that may be exercised by the grantor. A power of appointment basically means that the grantor has the power to change the ultimate beneficiaries of the trust, which the grantor may do under the grantor’s Will. By keeping this power, we ensure that a step-up in basis is preserved for the grantor’s children and that the grantor has the ability to change the beneficiaries so that if a child will not consent to an amendment, that child can be removed as a beneficiary and the grantor can change the trust with the consent of the remaining children.

While either spouse remains in the community, the residence will be protected from the costs associated with nursing home care. However, should nursing home or other skilled care become necessary, the residence is considered an available asset for Medicaid eligibility purposes and a lien may be placed on the home for the amount of Medicaid benefits received during a person’s lifetime. By transferring the residence to a Medicaid trust, the grantor should be able to protect it from the cost of nursing home care. The advantages of transferring the house in this way include the following:

1. The grantor have the right to remain in the house for as long as he or she lives;

2. The grantor retains the Star and/or Veteran’s Exemption for property tax purposes;

3. A tax advantage known as a “step-up in basis” (for income tax purposes, cost equal to the value of the residence as of the grantor’s date of death) is preserved for the grantor’s children or other beneficiaries;

4. If the house is sold during the grantor’s lifetime, the proceeds remain within the trust and can be used to purchase a new home with the original 5 year period applying to the new home; and

5. No gift tax is due at the time of the transfer.

The disadvantages of transferring the house include:

1. A penalty period would accrue based on the value of the home and the age of the younger spouse at the time of the transfer. Recall that if one applies within 5 years from the transfer that the penalty period will not commence until that time so it is important to wait the entire 5 years before applying.

2. The grantor will likely have difficulty if the grantor re-finances any existing home