July 30, 2018

Author: , HARRIS, FINLEY & BOGLE, P.C.

DESIGN-BUILD

If a builder has built a house for a man, and his work is not strong, and if the house he has built falls in and kills the house-holder . . .that builder shall be slain! Code of Hammurabi

Overview

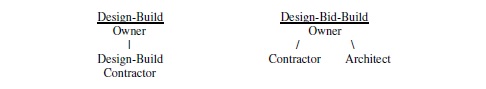

Design–build (or design/build or D/B) is a project delivery system used to deliver a project in which the design and construction services are contracted by a single contractor known as the design–builder or design–build contractor. In “design–bid–build” (“DBB”), the Owner contracts with the construction company in one contract and the design professional in a separate contract. Design–build, however, relies on a single point of responsibility. D/B proponents argue this project delivery minimizes risks for the project owner and reduces the delivery schedule by overlapping the design phase and construction phase of a project. Some commentators have stated that: “D/B with its single point responsibility carries the clearest contractual remedies for the clients because the D/B contractor will be responsible for all of the work on the project, regardless of the nature of the fault.” “Construction Contracts: Law and management” by John Murdoch and Will Hughes, published in 2007 by “Taylor & Francis E-library”, fourth edition.

Design-build is a method of project delivery that combines the design and construction functions and vests the responsibility for such functions with one contractor: the design builder. The Owner’s main duty is to define its needs by issuing its Performance and Design Criteria. One of the many distinctions between design-build and DBB is the level of design undertaken by the Owner prior to award of the construction contract and the level of specific, or prescriptive, criteria in the bid documents. Typically, under the DBB process there is an ongoing interaction between the Owner and the architect during the development of the design, thereby allowing the Owner to define and select many of the products and systems to be specified in the contract documents. Once the architect completes the design, contractors bid on the project.

Performance specifications and any plans to be included in the RFP generally are prepared by a design professional duly licensed or registered in the state. Owners should consider hiring a licensed design team to prepare the RFP, including those with mechanical and electrical engineering expertise, if critical to the project. Optimally, the design team should know the owner’s specific needs and desires.

Once retained, the licensed design team may assist with evaluation of the design-build team’s proposals as well as take a role on the owner’s behalf in providing oversight throughout project development. The licensed design team does not participate, however, on the design-build team. With design-build, Owners typically communicate their desires clearly in an RFP, specifying performance criteria in lieu of brand names and model numbers, leaving some of the decision making to the design-build contractor. Although certain project components may be specified as standards by the Owner, such as specific technology needs, security or heating and cooling equipment, the designbuild contractor will be required to provide a completed project that performs at or above the minimum performance specifications set forth in the design-build contract. The selected design-build contractor will complete the design documents to a level necessary to obtain required approvals and construct the project.

A DBB construction contract includes completed design documents. A design-build contract, however, will include performance criteria and possibly some design documents from which the design-build contractor will create completed documents. This basic difference in contract components broadly identifies the roles of the Owner and the design-build contractor. In a designbuild contract, the Owner clearly defines its needs and the expected level of performance, and the design-build contractor designs and constructs a completed project that conforms with those requirements.

While some see design as a modern delivery system, design-build is one of the oldest project delivery systems: “from a historical perspective the so-called traditional approach is actually a very recent concept, only being in use approximately 150 years. In contrast the design–build concept–also known as the ‘master builder’ concept—as been reported as being in use for over four millennia.” "Design-Build Contracting Handbook", by Robert Frank Cushman & Michael C. Loulakis, published in 2001 by Aspen Law & Business, USA ISBN 0-7355-2182-4.

Design-build entities are generally: 1) engineering and construction firms, with the ability to per form the required engineering, design, procurement and construction, 2) a joint venture of an engineering firm, 3) a general contractor, or 4) architecture. The “design–builder” is often a general contractor, but in some cases a project is led by a design professional (architect, engineer, architectural technologist or other professional designers). Some design–build firms employ professionals from both the design and construction sectors. Where the design–builder is a general contractor, the designers are typically retained directly by the contractor. A partnership or a joint venture between a design firm and a construction firm may be created on a long term basis or for a single project.

The Design-Build Institute of America (DBIA) states that design–build can be led by a contractor, a designer, a developer or a joint venture, as long as a the design–build contractor holds a single contract for both design and construction.

In design-build, the Owner provides performance specifications to which the design-build contractor then turns into the final designs. The design build contractor prepares a final design that meets the performance requirements but has wide latitude, although limited by industry standards, to select materials and equipment and to define the completed design details. Thus, the Owner has little input into the final design.

In general, design-build is best when the design and performance requirements are well defined and the detailed design and construction to be performed are widely known in the industry.

As such, the cost offered by the Design-Build contractor will be reduced as the Contractor will have experience to base his costs on. If the Owner needs to have an early commitment to an overall price, then D/B may be the best method. Projects that require special operations and maintenance requirements or other special needs may use another delivery method, particularly an approach that offers the Owner greater control over defining detailed design features.

Architects

After The Miller Act of 1935, there was a separation of design professional and the construction activities. This Act ensured the owner hired the Architect / Engineer to design the project, and the Owner hired the General Contractor to build the project.

Until 1979, the AIA American Institute of Architects’ code of ethics and professional conduct prohibited its members from providing construction services. The AIA has now acknowledged that design–build is becoming one of the main approaches to construction. In 2003, the AIA endorsed “The Architect’s Guide to Design–Build Services”, which was written to help its members act as design–build contractors.

In fact, the AIA has now issued Position Statement #26 AIA - Project Delivery: The AIA believes that every project delivery process must address the quality, cost effectiveness, and sustainability of our built environment. This can best be effected through industrywide adoption of an integrated approach to project delivery methodologies characterized by early involvement of owners, designers, constructors, fabricators and end user/operators in an environment of effective collaboration and open information sharing. The AIA also believes that an architect is well qualified to serve as a leader on integrated project delivery teams. The AIA further believes that evolving project delivery processes require integration of education and practice in design and construction, both within and across disciplines.

Two of the main contract issues for design professionals is their standard of care in D/B contracts and establishing their “Chain of Command.” Designers need to pay attention to the standard of care in the contract. Typically a designer’s standard of care is the degree of care that the average, similarly situated designer would employ. Further, in a typical DBB, the architect does not warrant the success of the completed project. In a D/B project, however, the designer may warrant that the project is successful. Thus, the designer may want to limit his/her standard of care and will want to pay attention to this part of the contract. Additionally, the architect will no longer report to the owner.

The architect should ensure the contract clearly spells out who has final authority over design decisions.

The possible advantages of design-build are as follows:

• Simplified contracting and contract administration:

There is one contract with the design-build contractor instead of separate contracts with an architect and a contractor.

• Cost containment:

The design-build contractor is under a contract to complete the project meeting the owner’s stated requirements within the contract price.

• Reduced number of change orders and disputes:

Errors and omissions in the design are the responsibility of the design-build contractor. Proper allocation of risks under the design-build contract reduces the potential for change orders.

• Reduction in adversarial relationships:

Designer and builder are teamed together, working under a single contract. This teaming can significantly reduce traditional conflicts and finger-pointing between designer and contractor.

• Cost savings:

Innovative, cost-effective solutions meeting performance criteria can be achieved.

• Time savings:

The design-build contractor is allowed the freedom to explore time-saving construction methods or systems while meeting the Owner’s stated criteria. Early communication between designer and builder can help prevent construction delays.

• Early cost definition:

Project costs are determined much sooner than with the traditional DBB process.

• Greater risk shifting and more efficient risk allocation:

A design-build contract can be written to assign appropriate risks to the parties most capable of managing them. The vesting of design and construction functions in one contractor allows for a much greater allocation of risk to the design-builder than in a traditional DBB contract.

• Alternative selection process:

Design-build contractors may be selected on the basis of factors other than price alone; therefore, design-build entities seeking to do future work with an owner have an incentive to perform well. Design-build also provides owners with the flexibility to develop an evaluation and scoring process that reflects the goals and needs of a specific project.

• Owner looks to one contractor for the entire project performance.

• The Owner can obtain an early commitment to an overall project price.

• Owner’s contract administration and site representative risks and costs are reduced, since the design-build contractor is responsible for all coordination efforts.

Some claim that design–build saves time and money for the owner, while providing the opportunity to achieve innovation in the delivered facility. They also note that design–build allows owners to avoid being placed directly between the architect/engineer and the contractor. Under design–bid–build, the Owner takes on significant risks because of that position. Design–build places the responsibility for design errors and omissions on the design–builder, relieving the owner of major legal and managerial responsibilities. The burden for these costs and associated risks are transferred to the design–build team.

The possible disadvantages of a design-build contract are as follows:

• Misconception:

Owners unfamiliar with the design-build process may have a preconceived idea that this method automatically eliminates change orders, expedites project completion, and saves money. As with any delivery system, the benefits that can be achieved, if any, are largely dependent on many things, including a high-quality RFP, an informed Owner, and a well-qualified design-build contractor.

• Inexperience:

Most Owners are familiar with their role under the traditional DBB method. Design-build requires different contracting and decision-making processes for Owners. Owners lacking expert legal and design assistance may face significant problems unless they are already familiar with the design-build process.

• Less control:

The design-build contractor is included in the process before plans are finalized. Owners entering into a design-build contract must allow the design-build contractor to make certain decisions that may have been made by the Owner on previous DBB projects. Failure to include in the contract specific requirements desired by an Owner may result in decisions made by the design-build contractor that do not meet the Owner’s needs.

• Potentially higher costs:

Whether design-build will be less expensive than DBB on a given project is unclear. Although designbuild efficiencies, design flexibility, and the ability to innovate that are afforded the design-builder are frequently reflected in reduced cost, increased risk allocation may result in a higher contract price that includes contingencies. Any savings realized by the design-build contractor may not be passed along to the Owner. Additionally, a design-build contractor that agrees to a guaranteed maximum price before receiving bids on the work may propose substituting less costly materials to offset bids that may be higher than anticipated.

• Increased public involvement and administrative tasks:

For governmental owners the law may require: (1) holding a public meeting to determine whether design-build is appropriate for a particular project; (2) preparing a qualification process; (3) establishing a labor compliance program or entering into a collective bargaining agreement; (4) reporting to governmental agencies project completion as well as complying with other governmental agencies.

• RFP preparation:

A significant amount of time, effort, and expertise is needed to produce the RFP. Translating the owner’s needs into clear performance criteria that provide sufficient specificity and appropriate flexibility is a difficult task and, if done improperly, may adversely affect any potential benefits of the design-build process. This point cannot be overstated.

• Potential for disagreement:

Because the design-build contract is based on performance criteria and preliminary design documents, the interpretation of these documents may be the subject of potential disagreement between the Owner and design-build contractor. Additionally, the Owner’s architect’s interpretation of the RFP plans and specifications may mean something completely different to the design-build contractor’s architect.

• Potential disagreement on the project inspector:

The Owner’s choice of an inspector generally is approved by the architect and structural engineer of record. Because the architect and engineer are a part of a team with the contractor, their opinions may be influenced by the contractor’s opinion.

• Expedited decisions:

After the design-build contractor is selected, decisions required of the Owner must be made more quickly than may be anticipated. Because the design-build contractor has a fixed schedule for design and construction, there may be little time for consultation with the Owner. Delays in making decisions may be costly.

_ Owner must develop and issue an early definition of the important design and performance requirements that it must have in the project.

_ Once the contract is issued, Owner relinquishes control of the detailed design selection and the construction process.

_ Since the price offered by design-build contractors are typically predicated on conceptual designs or performance specifications, the awarded price is likely to be higher than in a Design-Bid-Build process as the design-build contractor needs to include some contingency for design development risks and other unforeseen construction risks (unless the project is a commonly performed project with cost/schedule history). Design-build contractor is given the incentive to use the least-cost approach to maximize its profit, which could be contrary to the Owner’s interest.

Some claim that design–build method limits the Owner’s involvements in the design and allege that contractors often make design decisions outside their area of expertise. They also suggest that a designer—rather than a construction professional—is a better advocate for the Owner and/or that by representing different perspectives and remaining in their separate spheres, designers and builders ultimately create better buildings.

There are some key characteristics of design-build with a properly prepared RFP. They are as follows:

• Risk Shifting

The design-build method allows for greater shifting of risk to the design-builder, particularly in the areas of design defects, efficacy, and warranties. For example, errors and omissions in design documents are the responsibility of the design-build contractor. In developing the RFP and the designbuild contract, Owner should carefully assess project risks and determine whether they or the designbuilder are best able to manage those risks efficiently and cost effectively. Shifting of inappropriate risks to the design-build contractor that should be borne by the Owner in a given instance will increase

the design-build contract amount accordingly.

• Team Selection

Factors other than price alone may be considered in selecting a design-build team. Owners should ensure that the evaluation process and criteria are adequately described in the RFP in order to minimize the potential for protests.

• Schedule

Construction schedules may be shortened because of innovative systems and methods proposed by the design-build team.

• Cost Certainty

The cost of the project may be determined early in the process. The design-build team bears the responsibility for delivering the project for the contract amount.

• Decision Making

Much of the decision making during the completion of design development and contract documents and construction may be shifted from the Owner and its designers to the design-build team.

• Performance Criteria Compliance

Because the designer and builder constitute a team that will produce a completed project based on performance criteria established by the Owner, verifying compliance with the criteria is an important but difficult task. Complete RFP documentation can reduce the burden. Communicating facility requirements thoroughly enough to ensure compliance without limiting the design-builder’s creativity is a significant task. Using performance-based requirements and quality standards rooted in current construction practices establishes the design-builder’s responsibilities while accommodating flexible solutions and innovation. Because the design-build contractor’s cost proposal is not based on completed design documents, the RFP and design-build contract should clearly set forth the requirements, specifications, and allocation of project risks in order to avoid disagreements with the Owner that may arise over what was implied in the RFP. The design-build process does not eliminate the possibility of change orders created by incomplete or inaccurate information in the RFP package.

Inclusion of all relevant and necessary information is a good prerequisite for effective and optimal risk allocation. By the time an RFP is drafted, much information should be in place. The most critical part of the design-build process is the information describing the Owner’s needs and requirements, as well as the results of site surveys and geological investigations of the project site. The success of the project will be a direct result of the amount of preparation and information conveyed by the Owner. An Owner cannot expect specific elements or performance requirements to be included in the project unless they are made a part of the contract.

Change Orders

• In traditional DBB, contractor can ask for change orders if:

1) Changes caused by Owner – scope change, interference with work by Owner;

2) Change in conditions;

3) Design issues – (errors, omissions, ambiguities in the plans)

In D/B, the first and second classifications are still available to the contractor for change orders, but design issues/problems are generally not available. The reason is that the D/B contractor is responsible for the plans and specifications. Nevertheless, if the owners performance criteria is defective or has errors in the original criteria, the contractor may be entitled to a change order for the third classification.

Insurance/Bond Issues

• Design professional E & O policies usually exclude construction services.

• G.L. policies of contractors usually exclude professional services.

• Also performance bonds may not cover design services.

Warranties

• In DBB, contractor warrants its work, but not the performance of the project. This is because the design is not under the control of the contractor.

• In D/B, the design-build contractor is usually required to warrant the project’s performance. Some D/B contracts call for the design-build contractor to guarantee the operation of the project for a period of time.